While in Jerusalem, although we did not get to do much shopping due to the few days we were there and the amount we had to see. I did promise myself to by some traditionally embroidered clothing.

As you walk through the Damascus gates during the day the hubbub of vendors hits you, you see ladies selling their vegetables and farming goodies, an array of colourful clothing, cosmetics, toys and the list goes on.

The beautifully embroidered gowns caught my eye. I managed to purchase a few pieces. Coming from an Indian heritage, having beautifully embroidered clothes is not a new concept, but this embroidery felt different. I set off on a quest on the good old world web to get some answers and found some fascinating insight into the significance of these beautiful garments.

The beautiful cross-stitched embroidery is known as al-tatreez. Tatreez, or embroidery, is a Palestinian tradition deeply rooted in the history and culture of Palestine. It is a form of art and a language of expression. If we study the symbols and patterns of each area of Palestine, we can witness the connection of the Palestinian people to their land. Tatreez depicts not only the surrounding nature but also rites of passages and historical events.

While researching I stumbled upon a document exploring this beautiful embroidery written by Iman Saca and based on her mother Maha Saca research after she went out to Palestine to research the heritage. Both went onto start the Palestinian Heritage Centre in Bethlehem close to the Church of Nativity. Hopefully on my next visit to the country I would love to go explore more and visit.

‘In 1880 to 1948 working-class women in the villages, having perhaps more free time than spare money, developed locally distinctive ways of making and embellishing dresses and head coverings. Passed from mother to daughter, these embroidered patterns developed into local styles that were maintained for the better part of a century. After a lapse of decades, these traditions are being re-invigorated as a symbol of the Palestinian Past.’

Excerpt from Embroidering Identities (The Oriental Institute Museum of the University of Chicago)

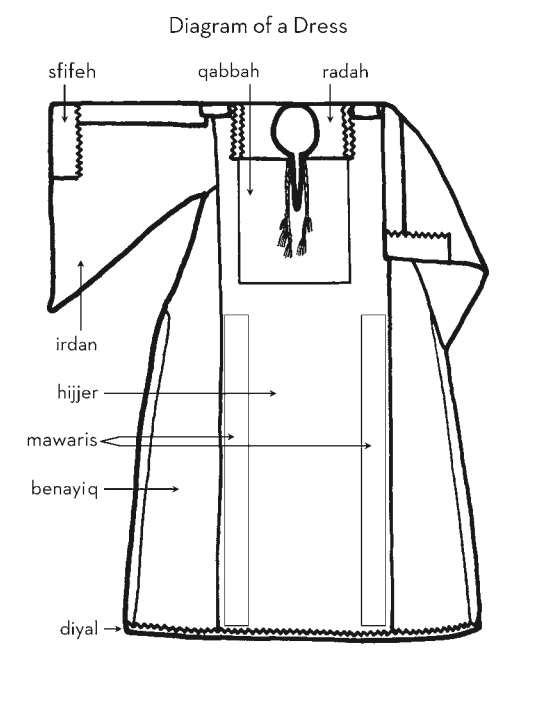

After purchasing some of my own Tatreez abaya. I noticed the long pointy sleeves and made the decision to get these taken in. Wondering what was the need to have such pointy sleeves. While researching I discovered that this part of the garment is called Irdan and women used to use the points to tie the sleeves at the back while they worked in the fields or around the house. Also, some women in Jericho used them to carry heavy objects or cover their heads. I made a swift decision after reading this to keep the pointed sleeve to preserve the reason behind it. Albeit more decorative for me now.

It was very interesting to discover how much thought goes into the different areas of the garment. Read through the links at the end to discover what each of the terms on the diagram below mean.

Reading through I discovered that women in each local region created the garments with distinctive embroidery that enabled people to establish the origin of the wearer. If you understood the embroidery you would know which region the wearer was from even as specific as the village. Women would show their marital status using the garments sending out messages dependent on their own mind-set at that moment. What is sad that today the distinctions have vanished along with the many villages that existed. Palestinian girls used to begin learning embroidery skills at the age of seven, they would start creating items for her wedding day. By the time, she married the dresses were lavishly embroidered.

After the establishment of Israel in 1948 there was a huge change in the social outlook of the region. Many Palestinian traditions were disrupted and people got displaced from the villages this tradition also took a massive hit. Many woman could no longer afford the time or money to continue this tradition. Some women did try to continue in refugee camps in Jordan and Lebanon in an attempt to preserve their identity.

Before the appearance of synthetically dyed threads, the colours used were determined by the materials available to produce natural dyes: “reds” from insects and pomegranate, “dark blues” from the indigo plant: “yellow” from saffron flowers, soil and vine leaves, “brown” from oak bark, and “purple” from crushed murex shells.

I then went on to research some more and came across a book that is available in the US called Tatreez and Tea.

Ghnaim unravels the stories of each dress and design by illuminating the experiences of her mother, Feryal Abbasi-Ghnaim, who learned embroidery from her mother and grandmother in mid-century Syria. Palestinian women have gathered together for generations with their daughters to work collectively on embroidery projects, bonding with one another over a cup of tea. Ghnaim’s mother found solace in continuing the tradition with her own daughters.

Through sharing her family’s al-Nakba story, and her mother’s stories of becoming a refugee in Syria and immigrating to the U.S., Ghnaim keenly exposes the necessity of continuing the endangered art of Palestinian embroidery to reconnect new generations of Palestinians to their homeland and by resuscitating its roots as a powerful, provocative and profound storytelling tool in modern society.

“Today, so much emphasis is placed on writing down the Palestinian experience; defining our identity and defending it, writing down our history and preserving it, and validating our existence in the mainstream. As a Palestinian in diaspora, I feel pressure to consistently and clearly articulate what my position is, who I am and what my people lay claim to. But for those of us who are at a loss of words, yet still have an expressive spirit that longs to practice an act of nonviolent resistance to oppression — we have an outlet that is not only indigenous, but therapeutic. When my writing doesn’t feel like enough, when my words are easily distorted, debated, and criticized, I turn to my art. I turn to my tatreez.”

Download your copy on Amazon here: https://www.amazon.co.uk/Tatreez-Tea-Embroidery-Storytelling-Palestinian-ebook/dp/B01L7KT7GO

Wedad Yassin on Tatreez:

Whenever I walk through the streets of Palestine, whenever I go to Palestinian weddings, I find elderly women wearing their hand-sewn thwab, their life stories intricately threaded onto their bodies. They always walk with such pride and confidence in their thwab. But that’s expected. After all, to ‘read’ a thobe is to read a lifetime of blood, sweat, and tears. Years spent climbing the same hills from one village to the next, decades spent tilling the soil under the sun — whatever the story is, whatever the experience is, it belongs to her, displayed in bold colours for the world to see.

When I was taking these photographs, one of the ladies jokingly asked if I was secretly trying to replicate her tatreez pattern.

Leish biddik itkalldi tatreezi?

I laughed and for a split-second thought about hugging her. It’s crucial to acknowledge that these hand-sewn thwab are like fingerprints. A pattern can be copied, but it could never carry the same significance that it does for the woman who stitched the original pattern with nothing more than a personal story to guide her hands.

Now you can buy Tatreez in most place in Palestine many using it to emblazon Palestine into tourism gifting to highlight the origins of where this beautiful embroidery and tradition came from.

Please feel free to read more in depth about this embroidery and what it meant and means to the Palestinian people. A tradition that they very much want to keep revive and keep alive. I am so pleased I purchased a piece of this tradition.

Some links you will find useful, also these are the many resourced I used to discover more:

https://oi.uchicago.edu/sites/oi.uchicago.edu/files/uploads/shared/docs/oimp25.pdf

http://www.tatreez.info/en/the-tatreez/

https://smpalestine.com/2014/05/27/tatreez-intricate-expressions-of-the-palestinian-experience/

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Palestinian_costumes

Leave a Reply